We don’t publish a lot of fiction — it’s hard to compete in the marketplace with the big names — but occasionally we find an author with a set of stories so relevant we have to go with it. Such was the case with Xujun Eberlein’s Apologies Forthcoming, a collection of short stories set in and around China’s Cultural Revolution. The tales are fictional but Xujun drew on her own personal experience of those times to write them. The book won the third annual Tartt Fiction Award in the US, and opinion on this side of the Pacific has been equally encouraging:

We don’t publish a lot of fiction — it’s hard to compete in the marketplace with the big names — but occasionally we find an author with a set of stories so relevant we have to go with it. Such was the case with Xujun Eberlein’s Apologies Forthcoming, a collection of short stories set in and around China’s Cultural Revolution. The tales are fictional but Xujun drew on her own personal experience of those times to write them. The book won the third annual Tartt Fiction Award in the US, and opinion on this side of the Pacific has been equally encouraging:

“Chinese-American authors such as Iris Chang and Amy Tan have made a significant contribution to factual and fictional literature, but few have a tale to tell as piquant as Xujun Eberlein’s.” — South China Morning Post

“Laudable in its own right, Eberlein’s collection is also a reminder of all the great stories that could and should be written in China today. Unfortunately, exile continues to be the home of China’s most honest and moving narratives.” — Asia Times

“With subtle political censure, Eberlein brings to life characters that draw out the helplessness, hope and heartache of the people who lived through the decade and its long, awful aftermath. The author has a way of delivering pathos that leaves a pang in the chest.” — Time Out

Below we print one of the eight stories from the book. In Feathers, a teenage Red Guard dies from wounds suffered in a clash between opposing factions, but her mother and sister hide her death from her doting grandmother.

Feathers

On Wednesday, three uninvited messengers came.

That morning, ten-year-old Sail was bending her head low over the square dining table, concentrating on making a paper-cut of a scene from The Red Detachment of Women, the model ballet. A few weeks ago, Sail’s big sister Jia, a Red Guard in the 3rd middle school, had brought home several paper-cut patterns, and the novel activity spread in the neighborhood like spring flu. With the same zeal they had collected Chairman Mao’s photo buttons a year before, the kids now made, collected, and traded paper-cuts of everything: revolutionary heroes, flowers, animals, and landscapes. They showed off their collections to each other and competed. Regardless of their parents’ political factions, the ones who collected the most patterns won the looks of admiration. Sail wanted to be the biggest collector of paper-cut art in the world.

Sail was home alone: Jia was in her school “doing revolution” and wouldn’t be back until the weekend. Their little sister Windy had gone with Gaga, their grandmother, to the countryside, to hide from the armed fights between two factions of the Red Guards. Her father was at work — or more precisely, was under the scrutiny of the Revolutionary Rebellion Team. Her mother, a school principal with no functioning school to run, had gone to a grocery store before it opened, to ensure an up-front spot in the long line.

About eleven a neighbor peeked in the window. Sail glanced up and saw Uncle Luo, the head of the Revolutionary Rebellion Team. “Are you looking for my father?” she said. “He’s not home yet.” The man’s eyes searched inside; he shook his head slightly and left without a word. There was something strange in his stern face.

About noon appeared three uninvited guests, all teenage girls of Jia’s age. Sail recognized one who wore a Red Guard armband as Jia’s close friend, nicknamed “Foreign Ginger” for her pale skin.

Sail jumped up, “Is my big sister coming home early?”

The three teenagers looked at each other, none eager to reply. Foreign Ginger said, “Where are your parents?”

“They’re not home. I’m in charge,” Sail said. “Does my big sister have a message for me then?”

Foreign Ginger said with great hesitation, “Your sister . . . she was wounded.”

“How? How bad is it? Where is she now?”

“She is in the hospital. No, not too bad. We came to fetch your parents.”

Sail exhaled in relief as her father walked through the door. All the girls fell silent again. “Sail, go to the dining hall and get lunch for our guests,” her father said after greeting the teenagers.

Sail obediently put a pan and a couple of meal pails into a basket and walked out. The July sun was directly over her head, scorching and blinding. Nothing really bad could happen on such a bright day.

*

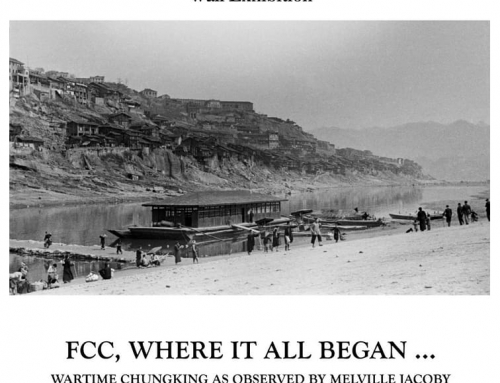

Sail’s family lived on the bank of the Jialing River near to its confluence with the Yangtze, and downstream from the 3rd middle school in a northern suburb. The three daughters were baby-named Jia, Sail, and Windy, results of their mother’s life-long romance with the river. When Mother gave birth to each, she looked out the hospital window, and used the first thing she saw for the baby’s name. Jia was born in winter, and Mother saw nothing but the Jialing River itself. Sail was born in spring when boats crowded the water. Windy was the consequence of Mother’s failed birth control. When baby Windy arrived in the world on a stormy summer day, Mother could hear nothing but the wind against the glass and see nothing but flying sand and rolling pebbles. The girls were 6 and 6 years apart in age, like the beginning of a neat number series. Between the oldest Jia and the youngest Windy, a recurrent cycle of 12 years of Earthly Branches was completed, so those two sisters shared the same animal symbol, Dragon, a respectful and worrisome Zodiac. Sail, on the other hand, was only an ordinary Monkey, with an ordinary face sandwiched between her two beautiful sisters. When she was little, Mother used to joke, Hey, was my Sail switched by the hospital?

Shortly after Jia’s birth, Gaga arrived from the countryside to help take care of the baby. She adored the Little Jia so much that she stayed. How could she not? In her whole life she had given birth to thirteen children in a small village, and none, except Sail’s mother, lived to see their first birthday. So Gaga began life a second time in the city, rearing one baby after another with great pleasure, while the babies’ mother was constantly busy running a school district and working as principal.

Sail knew why Windy went with Gaga — because her little sister could not fall asleep without clutching at Gaga’s flabby, empty bag breasts, Windy’s security blanket. When Sail was little she too liked to sleep with Gaga; Gaga had this clean fragrant smell like no one else, because she used only the Chinese honey locust tree pods to wash clothes, as the concept of soap was too new for her to trust. But Sail did not know why Mother kept her in the city with bullets flying around day and night. She wondered, but she did not ask.

*

Fifteen minutes later Sail returned with steaming rice in the pan and a couple of dishes in each pail. She paused at the door: her father was crying, collapsed on Gaga’s bamboo chaise. He never cried, not even when the Rebellion Team shamed him. He never sat on Gaga’s chaise either.

Jia’s friends were crying too. Sail quietly put down the lunch basket, took five bowls out of the cupboard, and spooned rice into each bowl. “Please have lunch,” she said in a normal voice. No one answered.

She handed a bowl of rice and a pair of chopsticks to each visitor. To her father she gave his blue-white china bowl, slightly bigger than the others. He took it and placed it on the floor beside him without looking. Foreign Ginger had just popped a clump of rice into her mouth, but seeing Sail’s father she put her bowl down beside the paper-cut of the woman soldier. The two other girls followed suit. The steam from the rice bowls wafted unattended; the girls avoided glancing at them.

Sail’s father got up with effort and said to the girls, “If you don’t want to eat, let’s go to the school now.”

“Am I going with you?” Sail said.

“No, you must wait for your mother. Tell her what happened and come with her.”

With these words he took to his feet, and the three girls quietly followed him out. Sail watched them disappear through the door of the courtyard.

*

Alone, she waited for her mother; it was impossible to do her paper-cut now. Sail tried to eat a bit of rice, but could not swallow. She was not sure what had happened, and did not want it made clear. She went to the courtyard door and peered down the noisy road several times, but her mother was not among the crowds. She must have been in a long line waiting to be yelled at by the grocery store workers. These days a grocery store worker was like a queen.

Half an hour passed; Sail decided to go look for her mother. She wondered if she should lock her door with the “iron-general” lock. Didn’t Gaga always lock the door when no one was left inside? She locked the door, put the key in her pants pocket, and went out to the street.

Two hours later Sail returned home exhausted, her shirt soaking in sweat and her wet hair stuck to her neck. She had gone to several stores and squeezed into every line to be cursed by frustrated grocery shoppers, but found no trace of her mother. At her door she gasped: the hasp and staple were pried out. Then she saw a grocery basket crushed on the ground, a few yellowed vegetable leaves littered around.

Aunt Tang, Uncle Luo’s wife, approached, crossing the courtyard. “Your mama said, ‘What a silly Sail, locking the door without leaving the key!’ ” Aunt Tang mimicked. “Then I told her, Jia is drowned, and she fell like this.” Aunt Tang opened her arms to topple backward.

“You made that up!” Sail said.

“Yeee! Am I like one to make things up?” Aunt Tang raised her voice. But when she saw Sail’s teeth bared like a cat, she stepped backward.

“The 3rd middle school called the office this morning! Your Uncle Luo answered the phone!” Aunt Tang said. Sail just stared at her. “Your mama’s gone to your sister’s school. Look at you. You better go wash your face.”

Sail considered walking to Jia’s school. She didn’t have a penny, and she could not take the bus. But how many hours would it take to walk? Jia rarely took the bus when she came home on the weekend. She walked, to save money, and to learn from the Red Army’s long march. “This is only a thousandth of the long march,” Jia once said. Sail wished she had asked her big sister how many hours it took.

*

She lay on her bamboo mattress, closed her eyes, and tried to think. The mattress was cool at first, but soon became uncomfortably hot on every spot she rolled to. She did not like that gossipy neighbor. She did not like what she’d heard. Drowned and wounded were two different things. Or perhaps Jia fell into the river, and the river took her to some point downstream, near home, and good-hearted strangers rescued her. I should take a nap, she told herself, and let Big Sister wake me up when she returns home.

When she awoke, outside was dark and inside was quiet. She looked at the double horse-hoof alarm clock on the nightstand and saw it was five in the morning. She got up, thirsty and hungry. When she left her house she did not lock the door. It could no longer be locked. There were still stars in the sky, and an occasional small breeze, but the air was already working up toward another hot day. She walked to the Number 2 bus line, where she had seen Jia off four days before. A long line had already formed for the first bus, but the conductor selling tickets was half asleep. Sail waited until the bus was almost filled. She hid her small body between several impatient men and sneaked on without incident. The crowded bus took more than an hour to arrive at Sha’ping terminal.

Sail ran across the dusty suburban street to the gate of the 3rd middle school. Inside the gate she ran toward the larger-than-life statue of Chairman Mao. At the statue she turned right to the three-story classroom building. In the second floor’s meeting room, she saw her parents sitting silently, surrounded by a crowd of teenage girls and boys. Mother’s eyes were swollen like walnuts. When Sail appeared at the door, her parents stared like they didn’t recognize her. There was no life in their faces. Sail looked around fiercely but did not see Jia anywhere.

“Where is my big sister?” she demanded.

Foreign Ginger emerged from the crowd, pulled her out to the hallway and whispered that Jia had already been buried the previous afternoon. The weather was too hot, she said.

“No—!” Sail screamed. “Where is she? I want to see her! I want to see her!”

Foreign Ginger started to weep. Sail charged into the meeting room again and shouted to Mother: “I want to see Big Sister! Take me to see her!”

Her father responded in a low roar: “Stop it! Your mother hasn’t slept the whole night! Don’t make her cry again!”

Then Sail heard Mother’s trembling voice, “Sail, my child, your sister’s coffin has been nailed. You can’t see her any more.”

“I am going to pry the coffin open!” Sail said. Mother choked with sobs, tears streaming down her cheeks like a broken chain of beads.

Foreign Ginger came up again and looked into Sail’s eyes. “Little sister,” she said earnestly, “Jia is a hero. She died for Chairman Mao.”

Sail stared at her. So it was all right for Jia to die?

That day Foreign Ginger gave her Jia’s diary. On the inside of the front cover was a hand-copied poem:

“Life is precious

Love is more so

For my belief

I let both go”

*

When Sail was little, four or five perhaps, Gaga used to tell her: Listen, Cute, if you dream of a dead person, if she asks you to go with her, don’t. Sail would snuggle at Gaga’s knees and ask, But, what if I like her?

Uh-uh, Gaga shook her furrowed cheeks, in the affectionate way she did. Not if you don’t want to die, Cute.

Why don’t I want to die, Gaga?

Your torso, hair and skin, are benefits from your father and mother. You die before they do, that is unfilial.

I’m filial to you, Gaga, Sail said eagerly.

Good girl. Gaga stroked Sail’s hair, with her work-worn palm, callused like a lump of old ginger. Sail could hear the sizzle of the static on her hair.

But when Jia appeared in her dreams, no such question was ever posed. Jia kicked a shuttlecock made of rooster feathers, or jumped around a rubber rope while singing. It was Sail who ended up asking to go with her, wherever she was. Jia never answered; she just turned to mist, leaving Sail to wake to blankness.

*

Mother kept herself in bed most of the time. At her better moments she would sit up, empty-eyed, and repeatedly chatter: “I shouldn’t have named her ‘Jia’ . . . then the Jialing River wouldn’t have taken her back. . . .”

Or she would say with a blind smile: “What a strong child, like a calf…” as if Jia were still alive.

She kept all the windows in the house open, day and night. If Sail wanted to close them on a rainy day, Mother would scold, “Stop! How can your sister find a way to get back inside?”

Jia, in the meanwhile, found easy access to Sail’s dreams.

No one told Sail how Jia died. From overheard words here and there, she pictured her sister swimming with Chairman Mao in the river, her shoulder-length black hair fading in and out of the brown waves.

*

A month after Jia’s death, the Red Guard factions ceased fire. Gaga and Sail’s little sister Windy returned home from the countryside. Mother managed to pull herself out of the river of grief she had sunk into, and took Sail to meet them at the port.

Gaga had brought with her big and small bags of red beans, green beans, broad beans, sweet potato chips, and sunflower seeds. Mother squeezed out a smile, said a few words of greeting, took the bigger bags, and handed a small one to Sail, then abruptly turned and walked ahead.

“What’s your ma’s hurry?” Gaga jolted along with her once-bound feet. Four-year-old Windy, cute as a doll with sun-reddened face, imitated Gaga like a parrot, “What’s Mama’s hurry?” and she sneaked a little hand into the bag of sweet potato chips. Gaga pulled her hand out and said, “Haven’t you had enough? You little naughty! This is for your sisters.” She turned to ask Sail, “Does your big sister come home this weekend?”

Sail pretended she didn’t hear. She ran ahead and caught up with her mother and whispered. Mother said, “Whatever you do, don’t tell Gaga. It’ll kill her.” Tears swelled up in her eyes.

“But…”

“Make up a story,” Mother said. She sped up again and it was hard for Sail to keep the pace with her. The August sun was too bright, it hurt her eyes.

“What story, Mama?”

Mother stamped a foot. “Don’t follow me so tight! Gaga’ll suspect!”

Sail twisted her neck to see how far Gaga was behind; instead she was startled to meet the dark eyeballs of her baby sister. Windy stood right before her, sucking a thumb.

“I heard, I’m gonna tell,” Windy babbled.

“Heard what? Tell what?”

“I heard, I heard!” Windy clapped hands and hopped around. “I tell Gaga, tell Big Sister!” Then she stood on toes and hissed, “But I won’t if you give me a new flower dress.”

Windy wanted a floral dress! As if this were a lollipop like other 4-year-olds wanted. Sail looked around a street full of pedestrians in gray, blue and military green, then glanced at her own patched, hand-me-down shirt. She was momentarily amused by Windy’s request, a smile almost opened. Then she looked up and saw Mother’s back hunched beneath many bags. Turning her head she saw 75-year-old Gaga behind them struggling to hurry with her inconvenient feet. Lowering her eyes she saw Windy’s thumb in her mouth again, her mischievous eyes twinkling. What was Sail going to tell Gaga?

Many years later Sail realized that was the moment her childhood ended, in the hot and blood-stink summer of 1968. Her maturity began with a big lie, at the age of 10.

When they arrived at their courtyard door, a neighbor was already waiting. Aunt Tang greeted them eagerly by saying, “Gaga, I’m so sorry about Jia. . . .” And Sail interrupted, “You are sorry about my sister joining the army? Is this a reactionary view or what?” She steered Gaga toward home and Gaga sighed, “Even the neighbor knows I’ll miss my Little Jia. You shouldn’t be so rude to her good intention.”

A flock of black crows landed on the roof. One made a raucous cry. “How inauspicious,” Gaga said, “Someone dead nearby?” Sail shook her head like a rattle-drum. “No, no no no,” she said.

That evening after Gaga went to bed early, tired after the long trip, Sail visited each and every family in the courtyard and told them the truth about her lie. Men shook their heads and opined various advice, while women wiped their moist eyes and promised to comply. But it was the children that worried Sail. She knew from now on she would have to keep an eye open even in sleep.

*

Before Gaga’s return, Sail once eavesdropped on Mother sobbing out to a relative that, when she arrived at the school, Jia looked as if asleep, but as soon as Mother began calling her name, white foam seeped out of Jia’s mouth. “She heard me, my poor daughter, she heard me. . . .” This seemed a sign to Sail that Jia did not really die; after all, Sail had never seen the body.

Sail began to look for Jia, on the streets, in stores, at mass meetings, as if fact and belief were unrelated notions. When she started middle school the next year, she spent months scrutinizing the faces of older girls in the noisy schoolyard. Only one made Sail pause: the girl’s cheekbones were a bit prominent, like Jia’s. She followed her everywhere: to her classroom, to the playground (where she jump-roped like Jia), to her bus station after school. The girl at first ignored Sail. Then one day she blocked Sail’s way and exploded, “Do I have four arms or eight legs? Why do you always stare at me?”

Sail flinched and mumbled, “You look like my big sister.” She showed her a photo, in which Jia wore a paramilitary uniform and held a book of Chairman Mao near her heart. The girl examined the photo and laughed, “You call that alike?” Then she looked at it again more closely and paused. “Hmm, she seems a bit like my cousin Xiaodi.” They became friends after that. Her name was Yingbo, reflection in the waves.

Sail told Yingbo about her lie to Gaga that Jia had joined the army and was stationed in Xinjiang Province. Her new friend asked why Xinjiang. It’s the farthest province from us, Sail told her, so Gaga can’t find out. “That’s weird,” Yingbo said, “my cousin is also a soldier in Xinjiang.” What she said did not surprise Sail. It actually gave her hope, in an inexplicable way.

*

One day in school Sail’s class criticized the “Petofi Club,” a counter-revolution movement in 1956 Hungary that almost overturned their Communist government and resulted in the Soviet Union’s decisive intervention. The teacher seemed most angered that the counter-revolutionaries had fouled the name of the great 19th century Hungarian patriot poet, who had inspired many Communist heroes to give their lives to the revolutionary cause. He went on to recite a famous poem of Petofi’s as an example:

“Life is precious

Love is more so

For our liberty

I let both go”

Sail now understood Jia had quoted Petofi in her diary, except one line didn’t match. After class, she ran to find Yingbo and asked if she knew about the poem. “The teacher’s version was right,” Yingbo said positively. “Your sister just switched one line.”

“But why?”

“Why? The Party already got us the liberty. It’s politically incorrect to use that word now.”

*

Every few weeks Sail wrote a letter in Jia’s name and read it to Gaga. They sat down on the narrow sun porch of their apartment, Gaga lying on the weathered bamboo chaise, squinting in the spring, summer, or autumn sun. Windy stuck a bamboo-claw into Gaga’s collar and scratched her back, and Gaga sighed with joy, “What a luxury, what a luxury.” Then she fell into an attentive quietness as Sail cut open the glued envelope. Illiterate Gaga had great respect for the written word. She nodded every so often to what Sail was reading, and each nod gave Sail warm encouragement, while Windy ran around Gaga’s chaise and Sail’s wooden stool. It was almost a perfect, happy scene, except Mother neither read nor listened to the letters Sail wrote. As for Sail herself, at times she believed the letters were real. More real than Jia’s death.

Sometimes Gaga asked questions such as Xinjiang Province’s weather and customs, whether Jia was kept warm and well fed, or whether there were battles along the borders between China and the Soviet Union. But the letters never reported anything bad.

Everything went well for two years; by then the letters began to “arrive” more sparsely, but unsuspicious Gaga only sighed occasionally, “When the bird’s wings grow hard, she’s no longer attached to the roost.” Then, one day after Gaga chatted with a neighbor, she said to Mother, “Old Wang’s boy came home for vacation. Isn’t it a time for Jia’s visit too?” Mother hurried to do things and left the question unanswered, only throwing Sail a glance.

*

Sail had never prepared for such a question. She drilled her brain so hard that she got a headache, still she couldn’t come up with an answer. She wished Jia were there to supply her with a brilliant idea, as she often had before. For days Sail wore a sulking face in school and at home, until Yingbo asked what was wrong. Sail told her friend the quandary. Yingbo said, “How hard could that be? Let my cousin come disguised as your sister!” It turned out that Yingbo’s cousin, Xiaodi, morning flute, was due for a visit home soon. Sail thought about Gaga’s aging eyes, how recently she had asked Sail to thread the needle every time before mending clothes. Yingbo’s idea might work. The only thing Sail worried was whether Xiaodi would go along.

*

Xiaodi showed up several weeks later. The day before, when Gaga heard Jia was coming home, she made fermented glutinous rice, her specialty and Jia’s favorite. She steamed a pot of sweet rice, and fanned the rice with a round cattail leaf non-stop. After it was cooled, she thumbed a hole in the middle and put in a granule of yeast made in her hometown. Then she covered the pot, wrapped it in a thick quilt, and placed it in a closet. Windy followed her every single step. “At this time tomorrow it will be ready,” Gaga said, “but we have to boil it before eating.” Windy smacked her lips.

The next morning, when Gaga opened the pot, a sweet wine fragrance filled the room, but her smile faded in an instant: a third of the raw fermented glutinous rice was gone. Sail and Gaga found 7-year-old Windy drunk in her bed, unconscious. “What’s to be done?” Sail cried out. Gaga shook Windy’s limp body, “Wake up, my little ancestor, wake up.” Sail knew Gaga was as scared as she was then — Gaga only called a child ancestor in anxiety. The next moment, Windy opened eyes and sat up and pointed to the door: “A woman soldier!”

Xiaodi walked in then. For a moment Sail thought she saw her big sister, the soldier she imagined when composing Jia’s letters. Xiaodi’s back was so straight, like a steel beam. Short hair tossed neatly into the green cap with a bright red star insignia, she walked in big strides. Windy jumped off her bed and shouted: “Woman soldier! Woman soldier!”

Gaga’s eyes squinted at the sudden sunrays pouring in from the open door: “Is that my Little Jia? Is that my Little Jia?”

“But she’s not my big sister,” Windy shouted into Gaga’s ear.

Sail froze. She just realized her mistake: she had not thought Windy would remember their big sister.

Xiaodi scooped at Windy. She smoothed Windy’s silky black hair and said, “Hello, little Windy.”

“How do you know my name?” Windy said.

Xiaodi smiled. “Isn’t this how your big sister calls you? I’m her friend,” she said. Oddly, her smile looked sad. Was this because of Jia? Sail wondered.

Gaga cupped Xiaodi’s hand and said, “You are Little Jia’s friend?”

“Yes,” Xiaodi said. “How are you, Grandmother? Jia asked me to see you for her.”

“Why doesn’t she come home?”

“She’s too busy, Grandmother,” Xiaodi said. “She’s been promoted and has big responsibilities.”

“My Little Jia is a commander now?” Gaga sobbed.

“Yes, Grandmother, she is an excellent commander.”

“Sit down, sit down, girl, tell me more about my Little Jia.”

They sat, like grandmother and granddaughter, and chatted about Xinjiang and army life. Sail served boiled rice wine and fried sunflower seeds, while Windy offered Xiaodi her only candy. At one point Gaga told Xiaodi what nice letters Jia always wrote home and Sail saw Xiaodi’s eyebrow leap. Gaga had kept the most recent letters under her pillow; now she asked Sail to show them to Xiaodi.

When Xiaodi was leaving, the sun was almost set. Sail walked her outside of the courtyard door and thanked her. Windy followed them like a tail.

“You could be a good writer,” Xiaodi said to Sail.

“Who wants to be a writer?” Sail said. Writers were the lowest social class then — the “stinky ninth.”

Xiaodi looked at her, and again Sail saw dejection in her pretty eyes, inconsistent with her soldierly bearing. Sail was no longer sure where this sadness had come from.

“I am a writer,” Xiaodi said matter-of-factly. Sail was surprised — she didn’t know the army had writers. Xiaodi turned, her soldier’s big strokes creating a flutter. Quickly she was disappearing from Sail’s sight. “Big Sister!” Sail called out.

Xiaodi’s steps halted. Sail ran to her; Windy chased Sail. “Are you coming back?” Sail asked, eyes foggy.

Xiaodi said sternly, “Your sister wanted you to be a soldier too, didn’t she?” She was quoting from a letter by Jia — Sail. “A soldier sheds blood but not tears,” she added.

Sail rubbed eyes with the back of her hand. “I never cry,” she said angrily.

Xiaodi’s voice softened. “I know. You are a brave girl. I’m not your sister. You know that, don’t you?”

Sail had to ask one more question that had been in her mind for quite awhile, and she did not know whom else to ask. “Is my sister a hero?”

Xiaodi hesitated, then said, “There are things beyond heroism. You’ll understand when you grow up.”

Windy galloped between them, like an alerted little dog, neck steered in one direction and then another, sniffing at the bigger girls. Sail grabbed her baby sister’s chubby hand and said, “Let’s go home.” But Windy stood stubbornly, her black eyes fixed on Xiaodi’s face.

Xiaodi said softly, “Little Windy, see you again, okay?” Sail took Windy to go home, her little sister looking back at Xiaodi.

Back at home, Sail heard Windy asking Gaga, “Why didn’t my real big sister come home?” The question was like a hand gripping Sail’s heart. She held her breath until Gaga said, “Cute, your big sister will be home someday.”

Gaga always called her grandchildren Cute, begining with Jia.

*

But the danger of exposure always hovered nearby. Rat, Uncle Luo’s son, a year older than Windy, had a crush on the little girl. One day the two kids had a fight over a fledgling fallen off the roof. Windy saw the hopping bird first but Rat captured it. Windy said it was her bird and Rat said it was his. A moment later Windy came home all teary, telling Sail, “Rat said my big sister is a swollen log in the river!” Sail covered her little sister’s mouth and looked around, relieved to see Gaga wasn’t inside. She offered Windy to play with her paper-cuts, and Windy refused; she offered to tell Windy a story, and Windy refused. Sail wished she could give her sister a toy or candy, but there was neither in the house. Nor in the stores. Windy kept crying and Sail could not afford to let Gaga hear Windy repeat Rat’s words.

She thought of a trick Jia had once told her: if you stretch out your arm, with rice in your open palm, and shut your eyes tight, sparrows will come to peck at the rice in your hand. Then if you close your fingers quick, you’ll catch a bird. Sail had never tried this trick herself. She shushed Windy, went out to the courtyard, and opened both arms to stand like a scarecrow. Sure enough, soon a couple of sparrows came down from the roof and hovered around the rice in her open hands.

“Why are your eyes closed, sister?” Windy asked.

Sail opened her eyes to signal Windy to be quiet, and right at the moment a smart sparrow pecked a grain of rice from her hand and flapped away. Windy laughed and shouted, “Again, birdie, again!” Rat ran out of his door and watched, his little sparrow connected to his thumb by a thread. He offered to let Windy play with the sparrow, and Windy flopped to him and forgot about Sail. Sail thought of Rat’s words, the swollen log in the river — was that what kids say about her big sister? Her heart ached and ached, an unlikely pain in such a young chest.

*

An inconceivable thing occurred the next day. Early in the morning, the whole courtyard was awakened by loud twitters. The power line above Rat’s window was covered with a dense mass of sparrows, screaming at the top of their lungs. The fledgling’s tender chirp echoed from inside Rat’s house, one sound following another. Neighbors stood watching and commenting in amusement, and excited children threw pebbles at the birds. The sparrows dispersed, gathered, dispersed again, and gathered again. Each time fewer returned, and the human onlookers gradually dissipated. By the end of the day, only two sparrows remained, and they could not stop crying.

“Poor papa-mama. Poor baby,” Gaga sighed.

Sail went to Rat. “They are the parents,” she said to the boy, “why don’t you give the baby bird back to them?”

“It’s mine!” Rat said.

Aunt Tang, Rat’s mother, made a tongue click. “Yeee,” she said, “who are you to scold my boy? Can’t you see he has nothing to play with at all? Are you as cold-hearted as your capitalist father, asking my son to give up his only toy?”

Across the courtyard, Sail’s mother called sternly, “Sail! Back home right this instant!”

*

The parent sparrows stayed on the power line one day after another. They kept crying, though their voices got smaller and smaller. Windy went to Rat’s house every day to check on and feed rice to the fledgling. Sail spent a good part of each day staring at the two crying sparrows. At last, one morning, they did not come back. Sail ran to Rat and asked to see the bird, but Rat refused.

She knew the fledgling was dead then. She ran to the courtyard’s garbage pit and found a pinch of sparrow feathers wrapped in a newspaper. Just feathers. She took the feathers home. She folded up a little box with white paper, and put the feathers in the box. She cut a strip of cardboard and wrote on it 鸟之墓 — monument of bird. She found a palm size spot of open soil in a corner of the courtyard and buried the box. After setting up the paper monument, she stood pondering how to explain everything to Windy. It would be another difficult moment. Yet she knew now it would come and pass like any point in time, regardless of her own turmoil, so she might as well treat it as fictional.

*

Xujun Eberlein keeps a blog at Inside-Out China

Leave A Comment