Any reviews of our books on Amazon are most welcome, but especially when they are as detailed as these ones.

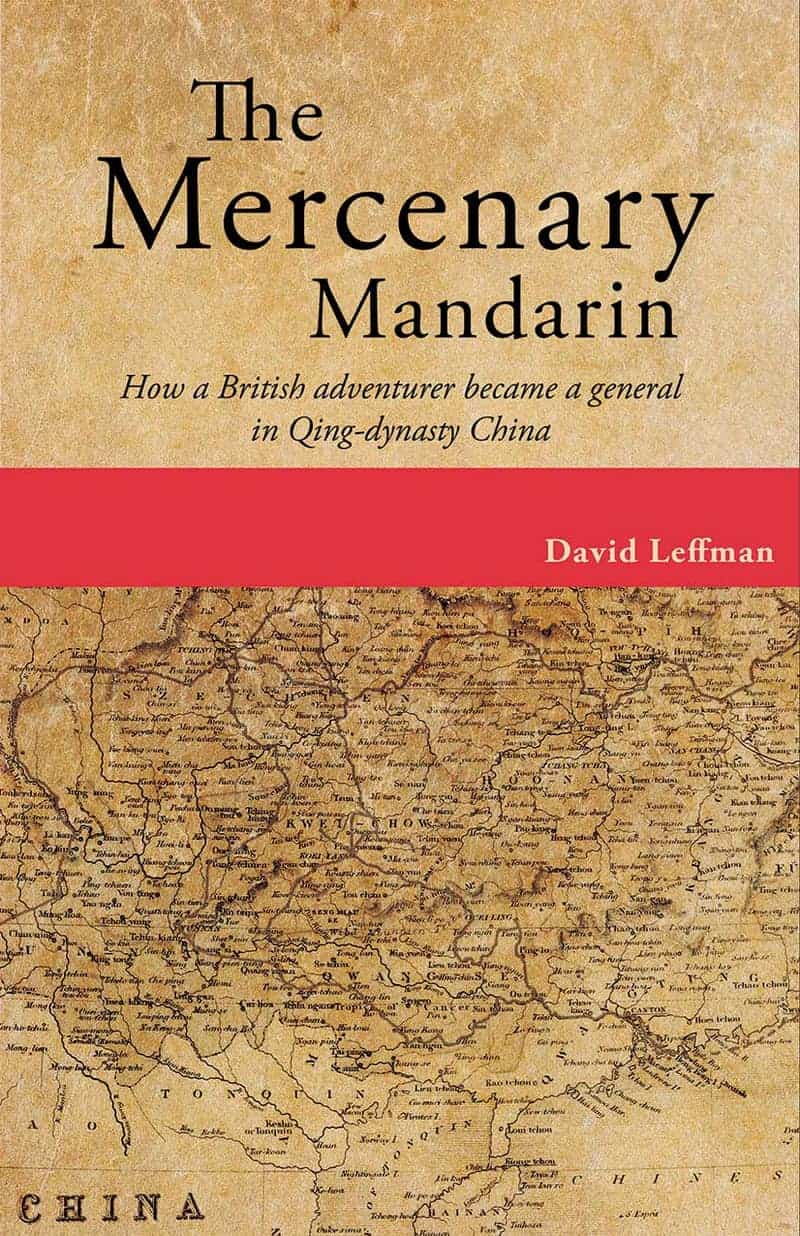

The Mercenary Mandarin (Amazon link

here) tells the story of William Mesny, a Jersey boy who ran off to sea and arrived in Shanghai in 1860 when he was just 18. Amid the chaos of civil war in 19th-century China, he became a smuggler, a prisoner of the Taiping rebels, a gun-runner and finally enlisted in the Chinese army, rising to the rank of general. Author David Leffman has spent 15 years retracing Mesny’s travels around China.

Traveling in China before the modern era of tourism was not for the faint-hearted. The country didn’t really have a tourism industry to speak of until the turn of the 21st century. Chaperoned group tours were available from the 1980s, but it wasn’t a very friendly place for the individual traveler or backpacker. I recall the lore about one Frenchman in the 1980s who dressed in Chinese clothes and swam his away across China in the Yangzi; the sight must have been so unbelievable that he couldn’t have otherwise gotten away with it. In my own travels in China’s northeast in the early ’90s, locals had to help me call up hotel after hotel in the phone book to find one that would accept a foreigner; in Changchun I ended up spending the night in a dorm-style inn for transient prostitutes which didn’t require registration.

With this finely written account of one particularly intrepid 19th-century adventurer, William Mesny, Leffman has helped to lay the groundwork for a more comprehensive history of travel in China. See Old China Books’ review [below] for an overall summary. I’d just like to point out the author’s attention to telling details. Note that Mesny was no vagabond but a mandarin official fluent in Chinese traveling in a sedan chair, a status earned through his years of aiding Imperial troops in the Miao Rebellion: roads unsuited for wheeled transport, inns so squalid Mesny and his retinue were kept awake all night scratching off vermin, guest rooms shared with livestock and no food to eat, their luggage ransacked or stolen, no standard currency to pay for anything (Mexican silver had to be exchanged for local coins after tiresome haggling), towns refusing entry to foreigners or attacking them, and the occasional hospitable welcome (more likely if a local magistrate hoped to sell him a daughter in marriage).

A book waiting to be written is a history of Chinese restaurants and dining practices, and Leffman enlightens us here as well, including one Chengdu teahouse “spattered in a mess of grease, dropped morsels, spilled sauces and discarded scraps,” or to quote Mesny’s travel companion Captain Gill: “the debris collects on the table more or less, though a person accustomed to these things… spits or throws it on the floor.” In the ’90s in Beijing, I similarly recall on restaurant tables the forests of beer and erguotou grain liquor bottles, toilet paper dispenser (in lieu of napkins), chicken bones, peanut shells, spent seeds and cigarette ashes, before all was swiped onto the bare concrete floor and finally mopped away before closing. Things have changed and you no longer see this. I kind of miss it — the former era when China was shocking and all the more memorable.

If I have any complaints, it would be to see more of these gritty details, and more in the subject’s own voice, who was after all a prolific writer and eccentric with a strong personality. Yet Leffman is oddly sparing in direct quotations. Without the benefit of having read Mesny in his own words, his character remains obscure and elusive, indeed rather flavorless, to me. Still, this is a vivid contribution to 19th-century Chinese history, from the perspective of one fearsome and tenacious expat.

Rising to the exalted status of Old China Hand is not easy – ask any of our latter-day China expats who aspire to that station. Most people today, let alone China expats, are not familiar with one of the earliest and most accomplished Old China Hands, the Englishman William Mesny. The tale of this swashbuckler, who started out in 1862 running guns up the Yangtze River to the rebels at Nanking and over the next 50 years became a general in the imperial Chinese army, an advisor to Chinese statesmen, and the author of an indispensable and near inexhaustible compendium of information about China and the Chinese of late imperial China, is told with flair and fidelity in David Leffman’s The Mercenary Mandarin.

For a fellow who himself traveled so much, Mesny could not have found a better biographer than travel writer Leffman, who dogged Mesny’s footsteps all over China for fifteen years researching his life in remarkable depth. Leffman’s account expands substantially the average reader’s exposure to the little known hinterlands of China, with descriptions of the country well beyond the confines of Beijing, Shanghai, and Canton, and delves into the history of 19th-century China in which Mesny played a significant role. The history related here, however, is so much less tedious for the disinclined because it’s told through the adventures of a foreign rogue.

In his forward, Leffman sets the tone for the adventure to come by relating some of his own unique experiences in Mesny country, the far west of China.

“Miao are hospitable people and outsiders at the event were dragged cheerfully into the chaos; before even entering the town I’d been stopped by a roadblock of women in festival dress and handed a buffalo horn of wine, knowing that if I touched the goblet I’d have to drain it. …Several attempts later… I was led through into Taijiang, fuzzy-eyed and reeking of spirits. The party lasted three days.”

The festival is called the Sisters Meal, an occasion for young girls to come down from the hills in their gayest finery and hunt for husbands, dancing in circles and singing “flirty, dirty songs” in falsetto. Leffman describes his early trips to China and the culture shock he experienced due to the unexpectedly rough conditions, and how over subsequent years of travel in China he was witness to the gradual changes that came to the lives of ordinary people. After once swearing he would never return to the country, his persistence (“bloody-mindedness”) over the years paid off, and his appreciation of the country advanced apace with the improvements.

In 1862 Shanghai, William Mesny rubbed elbows with the American freebooter Frederick Townsend Ward when Ward was recruiting for his Ever Victorious Army (EVA), but answered the sound of a different bell and navigated his own course to fame. We can speculate, however, whether if Ward had not died in 1862 but stayed on in China, he too might have achieved a notoriety similar to that of Mesny. And it is satisfying to find Leffman feels that many accounts overplay “Chinese” Gordon’s leadership of the EVA, which was created and developed by Ward, and Gordon’s involvement in the suppression of the Taiping rebellion – this is a welcome observation coming from a British author.

Read more of this review.

Our thanks to these reviewers and anyone else who has enjoyed the book. See more details at its product page.

Leave A Comment