Confessions of a Hong Kong Naturalist is a natural history memoir, tracing the journey from novice to expert of aspiring naturalist Graham Reels as he follows a trail of discovery into the miraculously fascinating and diverse world of Hong Kong’s wildlife.

Read this excerpt from his book. It is taken from Chapter 9, Far-flung Shores.

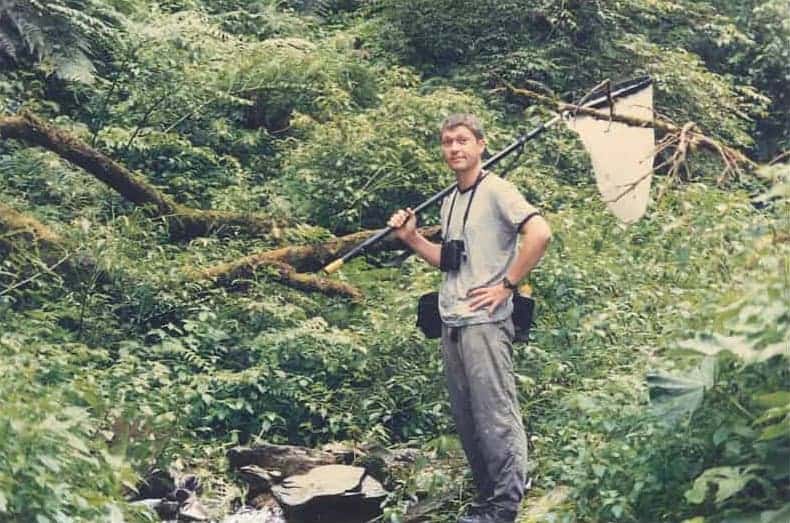

Graham says: “The background is that it is March 1996. My colleague Michael Lau and I have recently started working on a territory-wide biodiversity survey for Hong Kong University. This involves making inventories of birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and insects at scattered locations and is taking us to some very remote places, including the abandoned village of Pak Lap in Sai Kung peninsula.”

At Sha Kiu we walked up a trail to the ridge, going through shrubland in which I set a malaise tent and Michael his Sherman traps. Following the trail eastward over the headland, we descended to the abandoned village of Pak Lap. There was a nice beach there which reputedly was a favoured landfall site for illegal immigrants from China (still a big problem in the Hong Kong of 1996). We set more traps in marshy grassland at Pak Lap, hiked back over the ridge to Sha Kiu, and boarded our sampan again to travel the two miles to Bluff Island. The water was calm enough in the sheltered cove to get quite close in to the shore, before we jumped out and hauled our remaining equipment (light trap, fuel, tent, camping gear, malaise tents etc.) up the beach. The boatman waved goodbye in the growing gloom of the afternoon and we turned our eyes landwards.

At Sha Kiu we walked up a trail to the ridge, going through shrubland in which I set a malaise tent and Michael his Sherman traps. Following the trail eastward over the headland, we descended to the abandoned village of Pak Lap. There was a nice beach there which reputedly was a favoured landfall site for illegal immigrants from China (still a big problem in the Hong Kong of 1996). We set more traps in marshy grassland at Pak Lap, hiked back over the ridge to Sha Kiu, and boarded our sampan again to travel the two miles to Bluff Island. The water was calm enough in the sheltered cove to get quite close in to the shore, before we jumped out and hauled our remaining equipment (light trap, fuel, tent, camping gear, malaise tents etc.) up the beach. The boatman waved goodbye in the growing gloom of the afternoon and we turned our eyes landwards.

[Two days later]

Michael and I met up again at Sai Kung and disembarked from the sampan at Sha Kiu in weather which continued to be drizzly and a little blowy. We walked up and over the ridge to Pak Lap, inspecting the two malaise tents, which were still standing although barely any insects had flown into them (wiser than us, the insects had been sitting tight and doing nothing during the squally, cool weather of the past two days). We left the light trap and fuel in a sheltered spot in the shrubland on the Sha Kiu side of the ridge, and spent the rest of the day at Pak Lap, eking out what wildlife findings we could in the dreary weather. The most notable finding was of a leopard cat scat, which barely, briefly, lifted our spirits.

There was a row of half a dozen or so empty, long-abandoned houses in Pak Lap, set back from the beach. As it was still raining we thought it might be a good idea to sleep in one of these, and we found one which still had functioning wooden double doors, fastened not by hinges but by pegs on top and bottom which were set into pits in the ceiling and floor. The doors could be sealed from the inside by sliding two horizontal wooden beams into wooden brackets on the back of them. There was just room on the floor inside the house for two sleeping mats, and, rather handily, there was an old wooden table on which moth-pinning work could be done or food prepared in nice dry conditions. There were even a couple of candles for when it got dark. All in all it seemed perfect for our needs. We left our camping gear there and in the late afternoon traipsed back to the Sha Kiu side of the headland to set the light trap, not expecting great things in the steady light drizzle.

Back at the abandoned village house, we cooked up a tasty meal (probably canned Szechuan pork with instant noodles) before heading out for a little night surveying. Michael recorded a single species of amphibian, sufficiently unremarkable for me to have forgotten what it was (probably an Asian common toad or a paddy frog) but otherwise it was very quiet.

At about 10pm we again took the trail over the headland to the Sha Kiu side, to refuel the generator for the light trap, and then we returned to our cosy little house, pushed the doors closed and lit the candles. Outside, in the inky darkness, the rain was still falling.

We were chatting quietly over a cup of tea when, at about 10.45pm, we suddenly heard the sound of footsteps outside; heavy shoes crunching on the little bits of broken glass that littered the forecourt. Several sets of footsteps, but no voices. Then all went dead quiet. We looked wide-eyed at each other, in tense silence, remembering that Pak Lap was a notorious beaching point for Chinese illegal immigrants, many of whom were desperate and potentially dangerous. A dark rainy night such as this would be perfect for a furtive landing. Our visitors clearly didn’t want to be heard. The footsteps had come to a halt, seemingly, right outside our doors. Michael was sitting closest to them.

‘Slide the beams across,’ I whispered, gesturing at the locking beams which we had left unfastened on the doors. Michael stepped over quietly and slowly shot the bolts home, before stepping back and standing beside me as we both faced the doors. I had picked up my pocket knife from the table and was now clutching it tightly, determined that if this was to be the moment of my demise, I would not go cheaply, by God. Still, there was not the slightest sound outside.

Suddenly, a violent kick on the doors! They shuddered alarmingly. Michael and I, shoulder to shoulder, yelled our defiance. Another thunderous blow! This was it – the doors came flying in off their wooden pegs, crashing to the floor either side of us. I yelled again, brandishing my two-and-a-half-inch blade threateningly, and Michael shouted too, his fists at the ready, as four men burst into the house, themselves yelling, their torches flashing into our eyes.

Time froze for a split second. Thus did the two ecologists, bravely facing their foes, first perceive that their attackers were wearing police capes and hats. Thus did the four nervous policemen, courageously confronting a desperate gang of illegal immigrants, first realise that one of their targets, at least, was clearly not from China and probably not illegal, and his companion was obviously a local.

And then, quite spontaneously, everyone started laughing with relief.

After we had explained what we were doing there the police patrol good-naturedly shuffled out. As they were leaving, one of them solemnly advised us to beware of illegal immigrants in the vicinity, apparently oblivious to the irony of his imparting this advice after destroying the doors of our house. Fortunately, I checked the impulse to point this out to him and we parted amicably. The rest of the night passed without incident.

That story got into the papers. Fiona Holland, the reporter who had written the feature article on us for Eastern Express, was in touch with Michael a few days later asking if he had any news on the survey’s progress, and he duly obliged her. It was passed off as an amusing story, which it was of course, but at the time it had been rather tense. I was interested by what my own reaction had been: not fear, as I might have expected, but a raging, furious indignation at the threat to my person and to my friend. I had literally been ready to fight to the death. I was glad to have found that out about myself.

Leave A Comment